The pale winter sunlight shone from the high windows of the Cambridge University library onto a dark leather book cover. In the hall full of silent scholars, I opened it and leafed through picture after picture of men and women in familiar postures. Here was Warrior Pose; there was Downward Dog. On this page the standing balance Utthita Padangusthasana; on the next pages Headstand, Handstand, Supta Virasana, and more—everything you might expect to find in a manual of yoga asana. But this was no yoga book. It was a text describing an early 20th-century Danish system of dynamic exercise called Primitive Gymnastics. Standing in front of my yoga students that evening, I reflected on my discovery. What did it mean that many of the poses I was teaching were identical to those developed by a Scandinavian gymnastics teacher less than a century ago? This gymnast had not been to India and had never received any teaching in asana. And yet his system, with its five-count format, its abdominal “locks,” and its dynamic jumps in and out of those oh-so-familiar postures, looked uncannily like the vinyasa yoga system I knew so well.

Time passed, and my curiosity nagged at me, leading me to do further research. I learned that the Danish system was an offshoot of a 19th-century Scandinavian gymnastics tradition that had revolutionized the way Europeans exercised. Systems based on the Scandinavian model sprang up throughout Europe and became the basis for physical training in armies, navies, and many schools. These systems also found their way to India. In the 1920s, according to a survey taken by the Indian YMCA, Primitive Gymnastics was one of the most popular forms of exercise in the whole subcontinent, second only to the original Swedish gymnastics developed by P.H. Ling. That’s when I became seriously confused.

Ancient or Modern?

This was not what my yoga teachers had taught me. On the contrary, yoga asana is commonly presented as a practice handed down for thousands of years, originating from the Vedas, the oldest religious texts of the Hindus, and not as some hybrid of Indian tradition and European gymnastics. Clearly there was more to the story than I had been told. My foundation was shaken, to say the least. If I was not participating in an ancient, venerable tradition, what exactly was I doing? Was I heir to an authentic yoga practice, or the unwitting perpetrator of a global fraud?

I spent the next four years researching feverishly in libraries in England, the United States, and India, searching for clues about how the yoga we practice today came into being. I looked through hundreds of manuals of modern yoga, and thousands of pages of magazines. I studied the “classical” traditions of yoga, particularly hatha yoga, from which my practice was said to derive. I read a swath of commentaries on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra; the Upanishads and the later “Yoga Upanishads”; medieval hatha yoga texts like the Goraksasataka, Hatha Yoga Pradipika, and others; and texts from the Tantric traditions, from which the less complex, and less exclusive, hatha yoga practices had arisen.

Scouring these primary texts, it was obvious to me that asana was rarely, if ever, the primary feature of the significant yoga traditions in India. Postures such as those we know today often figured among the auxiliary practices of yoga systems (particularly in hatha yoga), but they were not the dominant component. They were subordinate to other practices like pPranayama (expansion of the vital energy by means of breath), dharana (focus, or placement of the mental faculty), and nada (sound), and did not have health and fitness as their chief aim. Not, that is, until the sudden explosion of interest in postural yoga in the 1920s and 1930s, first in India and later in the West.

When Asana Went West

Yoga began to gain popularity in the West at the end of the 19th century. But it was a yoga deeply influenced by Western spiritual and religious ideas, representing in many respects a radical break from the grass-roots yoga lineages of India. The first wave of “export yogis,” headed by Swami Vivekananda, largely ignored asana and tended to focus instead on pranayama, meditation, and positive thinking. The English-educated Vivekananda arrived on American shores in 1893 and was an instant success with the high society of the East Coast. While he may have taught some postures, Vivekananda publicly rejected hatha yoga in general and asana in particular. Those who came from India to the United States in his wake were inclined to echo Vivekananda’s judgments on asana. This was due partly to long-standing prejudices held by high-caste Indians like Vivekananda against yogins, “fakirs,” and low-caste mendicants who performed severe and rigorous postures for money, and partly to the centuries of hostility and ridicule directed toward these groups by Western colonialists, journalists, and scholars. It was not until the 1920s that a cleaned up version of asana began to gain prominence as a key feature of the modern English language-based yogas emerging from India.

This cleared up some long-standing questions of mine. In the mid-1990s, armed with a copy of B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Yoga, I had spent three years in India for yoga asana instruction and was struck by how hard it was to find. I took classes and workshops all over India from well-known and lesser-known teachers, but these catered mostly to Western yoga pilgrims. Wasn’t India the home of yoga? Why weren’t more Indians doing asana? And why, no matter how hard I looked, couldn’t I find a yoga mat?

Building Strong Bodies

As I continued to delve into yoga’s recent past, pieces of the puzzle slowly came together, revealing an ever-larger portion of the whole picture. In the early decades of the 20th century, India—like much of the rest of the world—was gripped by an unprecedented fervor for physical culture, which was closely linked to the struggle for national independence. Building better bodies, people reasoned, would make for a better nation and improve the chances of success in the event of a violent struggle against the colonizers. A wide variety of exercise systems arose that melded Western techniques with traditional Indian practices from disciplines like wrestling. Oftentimes, the name given to these strength-building regimes was “yoga.” Some teachers, such as Tiruka (a.k.a. K. Raghavendra Rao), traveled the country disguised as yoga gurus, teaching strengthening and combat techniques to potential revolutionaries. Tiruka’s aim was to prepare the people for an uprising against the British, and, by disguising himself as a religious ascetic, he avoided the watchful eye of the authorities.

Other teachers, like the nationalist physical culture reformist Manick Rao, blended European gymnastics and weight-resistance exercises with revived Indian techniques for combat and strength. Rao’s most famous student was Swami Kuvalayananda (1883-1966), the most influential yoga teacher of his day. During the 1920s, Kuvalayananda, along with his rival and gurubhai (“guru brother”) Sri Yogendra (1897-1989), blended asanas and indigenous Indian physical culture systems with the latest European techniques of gymnastics and naturopathy.

With the help of the Indian government, their teachings spread far and wide, and asanas—reformulated as physical culture and therapy—quickly gained a legitimacy they had not previously enjoyed in the post-Vivekanandan yoga revival. Although Kuvalayananda and Yogendra are largely unknown in the West, their work is a large part of the reason we practice yoga the way we do today.

Innovative Asana

The other highly influential figure in the development of modern asana practice in 20th-century India was, of course, T. Krishnamacharya (1888-1989), who studied at Kuvalayananda’s institute in the early 1930s and went on to teach some of the most influential global yoga teachers of the 20th century, like B.K.S. Iyengar, K. Pattabhi Jois, Indra Devi, and T.K.V. Desikachar. Krishnamacharya was steeped in the traditional teachings of Hinduism, holding degrees in all six darshanas (the philosophical systems of orthodox Hinduism) and Ayurveda. But he was also receptive to the needs of his day, and he was not afraid to innovate, as evidenced by the new forms of asana practice he developed during the 1930s. During his tenure as a yoga teacher under the great modernizer and physical culture enthusiast Krishnarajendra Wodeyar, the maharajah of Mysore, Krishnamacharya formulated a dynamic asana practice, intended mainly for India’s youth, that was very much in line with the physical culture zeitgeist. It was, like Kuvalayananda’s system, a marriage of hatha yoga, wrestling exercises, and modern Western gymnastic movement, and unlike anything seen before in the yoga tradition.

These experiments eventually grew into several contemporary styles of asana practice, most notably what is known today as Ashtanga vinyasa yoga. Although this style of practice represents only a short period of Krishnamacharya’s extensive teaching career (and doesn’t do justice to his enormous contribution to yoga therapy), it has been highly influential in the creation of American vinyasa, flow, and Power Yoga-based systems.

So where did this leave me? It seemed clear that the styles I practiced were a relatively modern tradition, with goals, methods, and motives different from those traditionally ascribed to asanas. One only has to peruse translations of texts like the Hatha Tattva Kaumudi, the Gheranda Samhita, or the Hatha Ratnavali, to see that much of the yoga that dominates America and Europe today has changed almost beyond recognition from the medieval practices. The philosophical and esoteric frameworks of premodern hatha yoga, and the status of asanas as “seats” for meditation and pranayama, have been sidelined in favor of systems that foreground gymnastic movement, health and fitness, and the spiritual concerns of the modern West. Did this make the yoga I was practicing inauthentic?

This was not a casual question for me. My daily routine during those years was to get up before dawn, practice yoga for two and a half hours, and then sit down for a full day researching yoga history and philosophy. At the end of the day, I would teach a yoga class or attend one as a student. My whole life revolved around yoga.

I went back to the library. I discovered that the West had been developing its own tradition of gymnastic posture practice long before the arrival of Indian asana pioneers like B.K.S. Iyengar. And these were spiritual traditions, often developed by and for women, which used posture, breath, and relaxation to access heightened states of awareness. Americans like Cajzoran Ali and Genevieve Stebbins, and Europeans like Dublin-born Mollie Bagot Stack, were the early 20th-century heirs to these traditions of “harmonial movement.” Newly arrived asana-based yoga systems were, naturally, often interpreted through the lens of these preexisting Western gymnastic traditions.

There was little doubt in my mind that many yoga practitioners today are the inheritors of the spiritual gymnastics traditions of their great-grandparents far more than they are of medieval hatha yoga from India. And those two contexts were very, very different. It isn’t that the postures of modern yoga derive from Western gymnastics (although this can sometimes be the case). Rather, as syncretic yoga practices were developing in the modern period, they were interpreted through the lens of, say, the American harmonial movement, Danish gymnastics, or physical culture more generally. And this profoundly changed the very meaning of the movements themselves, creating a new tradition of understanding and practice. This is the tradition that many of us have inherited.

Crisis of Faith

Although I never broke off my daily asana practice during this time, I was understandably experiencing something like a crisis of faith. The ground on which my practice had seemed to stand—Patanjali, the Upanishads, the Vedas—was crumbling as I discovered that the real history of the “yoga tradition” was quite different from what I had been taught. If the claims that many modern yoga schools were making about the ancient roots of their practices were not strictly true, were they then fundamentally inauthentic?

Over time, however, it occurred to me that asking whether modern asana traditions were authentic was probably the wrong question. It would be easy to reject contemporary postural practice as illegitimate, on the grounds that it is unfaithful to ancient yoga traditions. But this would not be giving sufficient weight to the variety of yoga’s practical adaptations over the millennia, and to modern yoga’s place in relation to that immense history. As a category for thinking about yoga, “authenticity” falls short and says far more about our 21st-century insecurities than it does about the practice of yoga.

One way out of this false debate, I reasoned, was to consider certain modern practices as simply the latest grafts onto the tree of yoga. Our yogas obviously have roots in Indian tradition, but this is far from the whole story. Thinking about yoga this way, as a vast and ancient tree with many roots and branches, is not a betrayal of authentic “tradition,” nor does it encourage an uncritical acceptance of everything that calls itself “yoga,” no matter how absurd. On the contrary, this kind of thinking can encourage us to examine our own practices and beliefs more closely, to see them in relation to our own past as well as to our ancient heritage. It can also give us some clarity as we navigate the sometimes-bewildering contemporary marketplace of yoga.

Learning about our practice’s Western cultural and spiritual heritage shows us how we bring our own understandings and misunderstandings, hopes and concerns to our interpretation of tradition, and how myriad influences come together to create something new. It also changes our perspective on our own practice, inviting us to really consider what we’re doing when we practice yoga, what its meaning is for us. Like the practice itself, this knowledge can reveal to us both our conditioning and our true identity.

Beyond mere history for history’s sake, learning about yoga’s recent past gives us a necessary and powerful lens for seeing our relationship with tradition, ancient and modern. At its best, modern yoga scholarship is an expression of today’s most urgently needed yogic virtue, viveka(“discernment” or “right judgment”). Understanding yoga’s history and tangled, ancient roots brings us that much closer to true, clear seeing. It may also help to move us to a more mature phase of yoga practice for the 21st century.

By Mark Singleton

Mark holds a PhD in divinity from Cambridge University. He is the author of Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice.

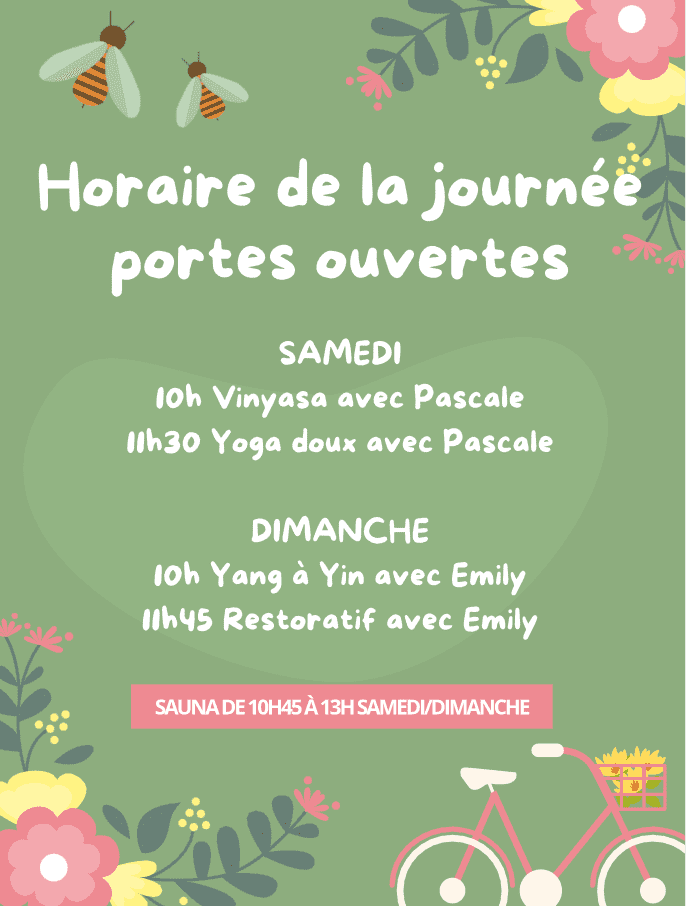

Nouveau! Nous changeons de plateforme pour Bsport

Nouveau! Nous changeons de plateforme pour Bsport